The Modern Merpeople Tales of Melissa Broder's "The Pisces" and Samantha Hunt's "The Seas"

A version of this article was published in Counterpoint's September 2018 issue in print and online.

Look, I didn’t set out to read a bunch of vaguely erotic feminist retellings of fairy tales this summer. It just kind of happened.

Okay, scratch that. It started with Angela Carter. Yes, I blame the deceased literary icon. At the end of my short stint in England studying the ever-indefinite topic of “birds in British literature,” my professor assigned me her novel, Nights at the Circus, which follows Sophie Fevvers, an acrobat who may or may not be part-swan, through the last months of the nineteenth century. I adored the oddities of Carter’s genre-bending narrative, which can move swiftly from social satire to fantasy to realism over the course of a single scene. Carter flew me from the inside of a London auditorium to the inside of a Fabergé egg so fast that my eyes became twisted and my mind narcotized. Though I was obsessed with Carter, Fevvers, and the literal and figurative masquerade of it all, I couldn’t exactly explain why.

Then, like many devoted Wellesley readers, I found myself in an argument with a friend, this time about whether Carter’s work was feminist or postfeminist. I agreed to read her assigned Carter text, The Bloody Chamber, a 1979 collection of short stories that retells the Brothers Grimm fairy tales from a feminist lens. Therefore, after a good old reimagining of “Bluebeard,” I feverishly fell down the faintly electrifying rabbit hole of “queer fabulism.”

Kit Haggard at The Outline recently coined this term from the fabulist literary tradition, where stories “make physical what is otherwise ephemeral or ineffable in an attempt…of understanding those things that we struggle the most to talk about: loss, love, transition.” Twentieth-century authors like Carter, Isabel Allende, and Barbara Comyns famously incorporated fabulist conventions, such as unexplained magical instances within real-world settings, into their fiction, but Haggard notices a new fabulist trend in contemporary literature. She notes that current writers like Carmen Maria Machado, Daisy Johnson, and Karen Russell have revitalized the fabulist genre with a focus on traditionally “queered” bodies. “These women have hit on the strangeness of occupying a queer or female body,” Haggard explains in her evocative article. “They’re making the world around those bodies strange as well.”

For a student fascinated by animality studies, mythology, and anything remotely sapphic, these contemporary literary trends are not simply exciting—they are deeply alluring. However, due to an unfortunate succession of fortunate summer events, I didn’t venture as far out to sea with my expeditions into Haggard’s “queer fabulism” as I would have liked. Nevertheless, of the books I did read, I happened to submerge into a pair of contemporary merpeople tales that, despite their similar folkloric roots, are as distinct as two seashells on a beach.

Even in the blessed air-conditioning of my home, I was burning as I read Melissa Broder’s The Pisces across from my mom at the kitchen table, so turned on that I had to mutter a quick “I have to go” before stealing away into my bedroom with my weird piece of literary fiction. Broder’s fiction contains some of the hottest scenes I’ve ever read, even though many of them happen on the cold rocks of the Pacific ocean, with a lost academic and a merman as lovers. Indeed, my feminist Chicago bookstore, Women and Children First, recommended The Pisces with three simple words: “GRATUITOUS FISH SEX.” Quite frankly, that review alone sold me on buying a copy during my 21st birthday party. But however funny The Pisces is (and, considering that Broder is the once-anonymous author of the Twitter @sosadtoday, it's downright hysterical), it is also intelligent, insightful, and unafraid to examine the depths of melancholia and shame.

Lucy, Broder’s 38-year-old narrator, is supposed to be spending her summer in a glamorous house on Venice Beach, writing her overdue dissertation on Sappho’s poetry, dogsitting her sister’s beloved pet, and attending group therapy for women who have recently been through disastrous experiences with men. Lucy’s own breakup left her on the side of the road, covered in jelly doughnuts after taking nine Ambien because she wanted “a peaceful way to just kind of disappear.” But the California oceanside immerses Lucy in another relationship, this time with a beautiful swimmer-turned-Siren. Theo, a living artifact from Homer’s Odyssey, appears sweet, but his concern for Lucy’s sexual pleasures—and his pessimism for his merman body—might be more sinister than it initially seems.

Though Broder’s plot epitomizes all that is fun about fabulist literature, her real treasure lies in Lucy’s inner monologues. As Jia Tolentino of The New Yorker explains, “people don’t have sex with sea creatures unless the world has failed them.” Lucy, motherless and meaningless, certainly feels like she’s a castaway of the universe. She intertwines her sense of self into her romantic relationships, spending an enormous amount of money on crystals to wish love into being and lingerie to impress shitty Tinder men. Simultaneously, Lucy understands that another person cannot fill up the hole in her life, explaining that “feelings were a luxury of the young, or someone much stronger than me—someone more at ease with being human.” Broder cleverly uses queer fabulism to make Lucy seem more nonhuman, unique, and otherworldly than she really is. When Lucy likens herself to Sappho, the comparison seems magical, except Lucy (wrongly) believes that Sappho threw herself into the very sea that reveals Lucy’s merman lover. Even Lucy’s dissertation, which attempts to assign meaning to the missing pieces of Sappho’s manuscripts, illustrates Lucy’s all-consuming obsession with her own emptiness. By forcing her protagonist to confront a living embodiment of the gap between story and reality, Broder illuminates the dangerous consequences of extending too much metaphor to everyday life. The melancholia, Broder implies, doesn’t come from the waves, the love stories, or the people who leave. Cliche as it is, the gap inside Lucy—and all those blinded by meaninglessness—hides the real beings that want to love her.

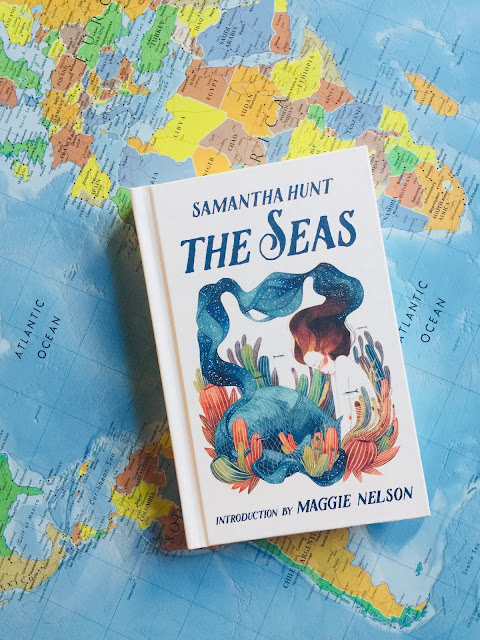

Samantha Hunt does fabulism somewhat differently from Broder and Carter, who force their readers to accept the magical aspects of their stories without question. In the oceanside town of her first novel, The Seas, an unnamed protagonist vehemently insists that she is a mermaid. She thinks she has eye issues because she can’t see past her love for Jude, an ex-soldier who recently returned from Iraq. She believes her father isn’t dead; he just went to his home in the sea. When she emerges from what appears to be a suicide attempt, she explains that she was simply “testing” her ability to breathe underwater.

Hunt doesn’t discourage her narrator’s reality, even if readers and her other characters do. “The world dismisses girls, stories and the imagination,” Hunt explained in a recent interview with Electric Literature, “I do not.” Hunt balances her story on the thin line between real and unreal, insisting that imagination and actuality together create fact. It helps, too, that the tiny world surrounding Hunt’s protagonist is almost stranger than the facts supported by her subconscious. No one ever successfully leaves the nameless town where the narrator lives. Her grandfather spends his days writing the world’s largest dictionary and organizing their family library by the way he feels about each book. The hotel where she works, which provides the novel’s title, names each room after famous hurricanes. In this dreary liminal space, it makes sense that a rock is actually King Neptune, or that someone could simply turn to water and disappear into the seas. No one can say it didn’t happen; it’s only by unjustly choosing actuality that the mind determines the imagination as the impossible.

The most evocative and rebellious scene of the novel comes at the end when the narrator and her mother have walked into the ocean together. Hunt’s narrator sees each wave crashing into her as words, evading the ones historically associated with women and jumping at the ones that she hopes to claim as her own. “Smelly” and “wait,” “hysteria” and “sad,” “stupid” and “suicide” are all abandoned while “lady,” “loaf,” “laughing,” and “title” are embraced by the mother and daughter. As “blue” and its definitions pass the narrator, she decides that “if one word can mean so many things at the same time then I don’t see why I can’t.” At its heart, The Seas demonstrates the ways that female and queer individuals can redefine the metaphors assigned to them by patriarchal society. “Call a young girl crazy,” Hunt explains. “Call her a slut. If she is creative, if she is free, she will learn to make something new from that old cloth.”

These two modern-day merpeople tales might conceptualize mythology in their own ways, but they similarly use the unreal to examine the inner lives of bodies who feel strange in a world that marginalizes them. It’s sad when these stories, and others like them, don’t seem to get as much attention as similarly themed-literature written by cisgendered men. In the literary world, David Foster Wallace and Junot Díaz continue to be praised for their works of melancholia and magical realism even though they have been accused of sexual assault and harassment. “Mermaid sex” might seem trivial until it's recognized as a way to, literally and figuratively, “eat men,” as both Broder and Hunt describe passionately in their novels. Moreover, these fabulist subversions demonstrate one way to demolish racist, sexist, and transphobic conceptions of what a body really is. When we fix and devour the queer fabulist tales of The Seas, The Pisces, Her Body and Other Parts, Everything Under, and more, we recognize a mystic literature that undermines problematic narratives by constructing new meanings out of the old tales.

Comments

Post a Comment