A Cup of Tea(rs) in Rupi Kaur's "Milk and Honey"

I was cleaning out my dorm room at Wellesley last Monday evening when a New York Times alert appeared on my phone.

“Fatalities have been reported at an Ariana Grande concert in England, where fans say an explosion was followed by a mass scramble.”

I took a screenshot, alarmed, and sent the photograph to my friend Olivia.

“Fatalities have been reported at an Ariana Grande concert in England, where fans say an explosion was followed by a mass scramble.”

I took a screenshot, alarmed, and sent the photograph to my friend Olivia.

“Holy shit,” I sent. Olivia, currently abroad in England, was set to see Ariana in London that Friday before coming back to the States. She had planned her plane tickets around the concert. I knew most certainly that Olivia was not at the concert that night—we had just video-chatted an hour earlier—but I still checked my phone anxiously until she responded.

We would later learn that a different Olivia had died in the bombing, along with 21 other attendees of the concert. ISIS has taken credit for the suicide bombing outside of Manchester Arena, one that countless writers have pointed out to be a clear attack on young women. I knew this the moment I saw the news that the particular placement of explosion was no accident. I told peers the next day over and over, “No straight grown man goes to Ariana Grande unless he’s with his daughter or girlfriend.” Teenage-girl-culture had been targeted, plain and simple. I wish I could say that I was surprised.

“I’m glad you weren’t there,” I told Olivia that night. I meant, I’m glad it wasn’t you.

Because it easily could have been.

~

That evening, I started reading Rupi Kaur’s milk and honey. I was in love with it instantly, but I was also surprised by how much it reminded me of my most previous experience with poetry. I hadn’t read a full collection of poems since my first semester in college, when my class studied Rita Dove’s Mother Love. Dove’s collection, which adapted and complicated the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, fascinated me with its chained sonnets, dark beauty, and commentary on modern motherhood, daughterhood, and womanhood. I could not help but draw comparisons between Kaur’s new work and Dove’s from twenty years ago.

The first contrast, though, was shameful and saddening. For I knew one of these works was destined for a college classroom—and that one would perhaps never make it.

~

|

| From Poetry Magazine, October 1992. |

Rita Dove’s poems in Mother Love discuss sexual awakening, rape, mother-daughter relations, first love, broken love, and the blossoming of womanhood, a blooming that she presents as both wonderful and tragic, dry yet vivid. She manipulates the traditionally masculine sonnet form to reveal and control its cage-like existence in poetic history. Though her work is powerful, it is immensely difficult; there is no statement in her works that simply reveals her message. Dove’s collection is a puzzle for young literature enthusiasts, a December finale for young women in their introduction-to-the-English-major class after a semester of Shakespeare and the Petrarchan woman. It is not a book that young people pick up for a read on their vacation.

But the similarities between milk and honey and Mother Love are striking. The simple language, the intense images, the discussion of sexual pleasure and blossoming we see in 1995 Dove comes up again just as powerfully in Kaur today. Kaur’s modernization, of course, is evident; her details of intercourse and her awareness of female bodies are much clearer than Dove’s are. Kaur’s first-person voice is all the more personal too, for Dove’s switching of pronouns, though complex, allows her to distance herself from her poetry. In a way Dove does not, Kaur claims her story in an act that encourages her readers to do the same.

What I perceive as Kaur’s strengths are what I know some university professors and literary critics would claim to be her weaknesses. Her poems are clear, short, soulful, gorgeous odes to young womanhood, first love, heartbreak, and bodies of those considered “other” in literary history. Though it can be complicated, Kaur’s work does not necessarily have to be deeply analyzed like Dove’s does. It is accessible—to literary lovers, yes, but also to non-English majors, to non-critics, to people from all educational backgrounds, to teens and adults, to people of color, to women. Her work is for them.

And yet, my favorite things about Kaur’s work, like its simple elegance and messages of strength for those who need it the most, were the aspects which would, ultimately, keep it unwelcome and disrespected in certain spaces. I was overjoyed to see milk and honey on the bestseller shelf at Barnes and Noble last week. I know Kaur’s work has been praised by reviews on HerCampus, Publisher’s Weekly, and Buzzfeed. Kaur does have 130K Twitter followers. milk and honey is a New York Times bestseller. But I could not find a full review of Kaur’s work at the Times. I could not find critics who gave her the praise she deserved. When I searched for that analysis and acclaim that I wanted Kaur to have, I turned up with very little.

Some might ask if that acclaim and focus actually matters, especially when Kaur’s poetry is clearly being read by many people. The truth is that I don’t want it to. But I’m me: a female English major and Education minor at an women’s college who knows far too well how quickly intelligent voices of youth, people of color, women, women of color, and especially young women of color can be silenced by media and scholarship that are, as liberal as they might claim to be, still sadly dominated by white cisgendered men. I would be lying if I said that they don’t still have power over our classrooms and newspaper articles.

Do those people matter? To people who are going to read poetry anyway, who visit the bookstores, who actively look for voices that are silenced, no, people in power are not going to stop them from reading. But for people who listen to media and institutional power, who still mock teenage girl culture, who are teenage girls that don’t consider themselves readers or have full access to literature or the Internet for whatever reason, the dominant voice is all the more powerful today. Just look at our American president. Just look at the faces of fifteen-year-old Olivia or eight-year-old Saffie, who died last week because people did not acknowledge their power or their voices. Did we throw the bomb on the 22nd? No, but when we made fun of Ariana Grande, when we mocked the simple elegance of female blossoming into self, when we did not give Rupi Kaur the acclaim she deserves, we enforced the idea that young women and people of color are silly, don’t matter, and don’t need security. We forgot how significant they are, how scary people might find them.

And then, we lost some of them.

~

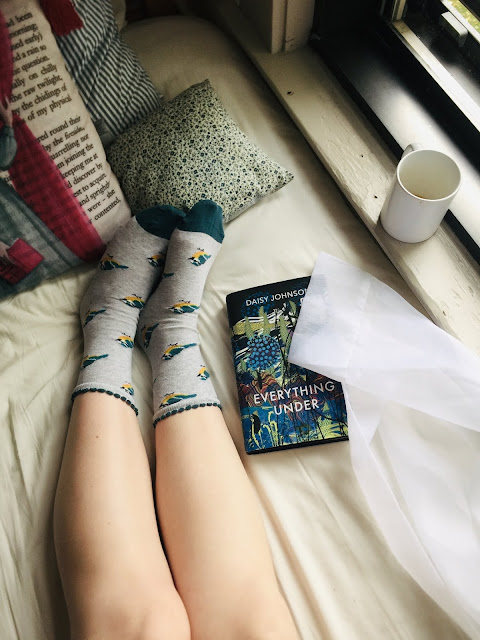

I cried on the airplane reading milk and honey. I cried until I smiled.

When I see Olivia this Sunday for the first time in four months, I will hug her just a bit tighter than I would have. I’m sure we will listen to Harry Styles and consume YA literature and attend Elizabeth Warren lectures with the same fiber and excitement that we did before. But I know that the faces of those young girls lost will hang like baby mobiles in our minds long after we have daughters of our own. We were bound to cherish them before May 22nd. We would have read them Dove and Kaur and Bishop when they were in our wombs, pulled out Harry Potter on their sixth birthday, danced with them to our classics Taylor Swift and Hamilton. We were bound to respect them anyway.

We just know even more now that the world still might not.

Author's Note: Let's encourage young female voices. You can follow Rupi Kaur on Twitter @rupikaur_ and you can read Olivia's own literary blog, The Book Tote, for more book enthusiasm.

Author's Note: Let's encourage young female voices. You can follow Rupi Kaur on Twitter @rupikaur_ and you can read Olivia's own literary blog, The Book Tote, for more book enthusiasm.

Comments

Post a Comment