How Daisy Johnson's "Everything Under" Rights the Footing of "Oedipus Rex"

Before I started Daisy Johnson’s debut novel Everything Under, I had categorized it in a subgenre of feminist literature that retold the story of Persephone and Demeter. Like Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Ode to Silence” and Rita Dove’s poetry collection Mother Love, the title Everything Under, to me, had to refer to the Underworld, which Persephone calls home after Hades kidnaps her from her mother. I assumed that, because Johnson’s retelling of a classical myth was about a mother and a daughter, it had to be that story. But like Persephone, I had fallen into the narrative trap that Johnson wants to undermine in her book. Though she leads her readers gently through her plotlines, I was still tripped up when I realized it was the story of Oedipus, not Persephone and Demeter, that Johnson had translated into a contemporary novel.

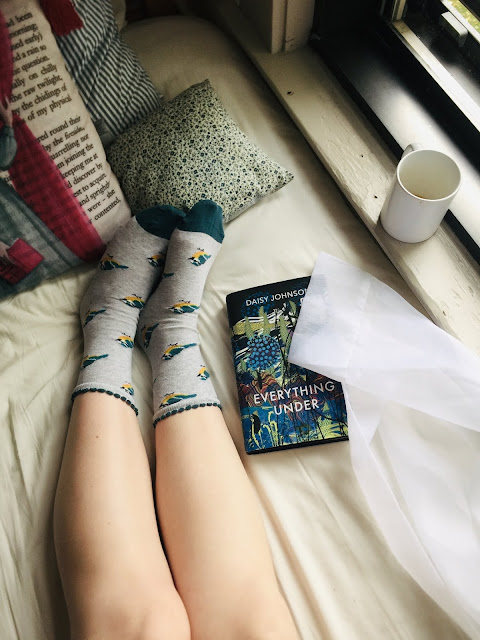

Johnson’s reinterpretation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, which tells the story of a Greek hero who kills his father and marries his mother, made her the youngest person ever to be shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. The then 27-year-old lost to Anna Burns’ Milkman this October. But I believe Johnson should have won. Retelling any piece of literature in an innovative way takes great skill. Retelling Oedipus Rex, a text known for its patricidal and incestuous protagonist, and making it about a relationship between a peculiar woman and her estranged daughter, is an impressive feat. Nevertheless, Johnson elegantly reworks a narrative that resists a modern retelling.

Johnson’s protagonist Gretel last saw her mother Sarah at a bus stop when she was sixteen. Sarah didn’t get on the bus with her daughter, and Gretel still doesn't know why. Now an adult, Gretel works as a lexicographer, researching and rewriting definitions for the Oxford English Dictionary. Meanwhile, she tries to suppress her own jumbled past, remembering only watery details of the childhood she spent on a houseboat. Mostly, Gretel recalls words—the ones she and Sarah crafted on the river north of Oxford, the ones that left Gretel lost in translation when she entered foster care as a teenager. She also remembers Marcus, a boy who lived with them one month, whom she played with—and fell in love with. She thinks there might have been a river monster—they called it the Bonak—that tried to attack Marcus and Sarah that winter, but she can’t be sure anymore.

A mysterious phone call forces Gretel to confront her past and its elusive cast of characters: Sarah, Marcus and his parents, and Fiona, Marcus’ family friend who might know what connects them all. Johnson tells us their stories without regard for chronological order, jarringly moving from present to past to more recent present to a past before the first past, going every direction to reach a terrible destination. It’s prophesied that Oedipus, whoever they are in Johnson’s story, must kill their father and marry their mother. But Johnson’s non-linear plot is confusing, even for a practiced reader.

Johnson’s timeline isn’t the only thing that’s baffling: I’m still unsure what I would call Johnson’s choice of genre. I went from being certain it was realistic fiction, to wondering if it was magical realism, to turning back to my original assessment of realistic fiction, and then doubting myself again. From one moment to the next, it’s unclear what actually happened all those years ago on the water and what Gretel and Sarah just dreamed up, playing off of each other’s imaginations and linguistic inventions. Even Gretel’s name, pulled straight from “Hansel and Gretel,” is simultaneously illuminating, as Johnson’s novel explores all that is folkloric and horrific about Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and confusing, as there might be more than one Gretel. Johnson’s writing deliberately lacks clarity. Despite my momentary frustrations, I found her murkiness perfect for her subject matter. She displays the truth in plain sight as she distorts everything alongside it, making her readers question reality even when it is described right in front of their eyes.

By retelling Oedipus Rex as a story about motherhood and womanhood, Everything Under focuses on anything other than the man in its source text. Johnson looks under what is socially constructed—our bodies, our language, our histories—to try and find what is innately human—our love, our fear, our “home,” wherever or whatever that may be. Through her misfit characters, Johnson considers how people who aren’t male or cisgender function—or can’t—in a world that wasn’t built for them. Sarah never wanted to be a mother, so she leaves her daughter behind. Marcus, who was once called Margot, abandons one family and tries to join another as his true self. Oedipus Rex wasn’t written to include women or trans people, but Everything Under focuses on characters who don’t fit into the identities placed upon them. Rather than choosing a vaguely matriarchal myth like “Persephone and Demeter,” Johnson forges a quiet rebellion through sexist classical literature to search for feminist truths.

However, even on the isolated river, Sarah and Marcus are still forced into the prison of conventional English, which inherently oppresses those deemed “other.” Though a homemade language cannot provide a permanent escape from patriarchal structures, Gretel and Sarah’s invented words are powerful enough to influence their personal reality. By making the metaphorical literal, Johnson transforms Gretel and Sarah’s words into spells to show how language can premeditate real life interactions. Their monster, the Bonak, seems to come to life beneath the river waters. It doesn’t matter if, as Gretel asks, she and Sarah “created the Bonak.” Their terror was real, even if their words, and their monsters, were not.

In a year where words seem to mean everything—where people aren’t people in the eyes of U.S. national policy if they are immigrant, transgender, black, or woman—Johnson’s Everything Under reminds us that language means nothing and everything at the same time. We make words, just as Gretel makes definitions, yet they often control us, limit us, and define us. We invented the words mother and child and prescribed a role to each party, but we don’t decide the relationship between a mother and a child. Still, these individualities are too often ignored to conform to a universal—and therefore, white, heterosexual, and middle-class—construction of motherhood. Why else are children ripped away from their parents at the Mexican border? Why else do senators think they can dictate whether or not a woman is ready to become a mother? Words and narratives predicate our lives, for better or worse.

Too often, too, we forget these underlining narratives even as we resist them. Take me and my instinct to make Gretel Persephone, to fall into a story that Johnson isn’t even rewriting. “The places we are born come back,” Gretel reminds Sarah, and Johnson reminds the reader, in the prologue to Everything Under. “If we were turned inside out there would be maps cut into the wrong side of our skin. Just so we could find our way back. Except, cut wrong side into my skin are not canals and train tracks and a boat, but always: you.” Unlike Oedipus, Persephone, and me, Gretel stops herself from slipping over her feet and falling into the narrative that seems prescribed for her. Through her, Johnson tells us that the constructed pieces of our lives, the language that society has decided describes us—our manmade canals, train tracks, and boats—might influence our identities; but they aren’t inherent parts of ourselves. We must look underneath our metaphors to find the things that make us who we really are.

Comments

Post a Comment