Let's Talk About Children's Literature

Let’s get one thing straight: I was a lame child reader.

It is not that I did not read, because I certainly did. I adored books. My father brags to other parents about how he had to make me stop reading to do things, arrogantly smirking at their own video-gaming children. My seventh grade teacher told my mother she worried I was “antisocial” because I spent much of my free time reading novel after novel. I distinctly remember a certain shelf in my Catholic elementary school library filled with books I was obsessed with, ones I took out over and over again to devour ruthlessly, in the same way that I today watch the same cold open from The Office. ‘Oscar, save Bandit,’ shouts Angela, before she throws her cat into a ceiling air vent that seconds later falls through that same ceiling. Iconic, and memorized.

Except, of course, I devoured white-bread, American cheese, little girl lunch box serials. I read the American Girl historical novels. Over, and over, and over again.

Don’t get me wrong: American Girl was fun for me as a kid. I loved those characters and, consequently, their doll counterparts. I loved their formulaic stories, a school one, a happy birthday one, a Christmas one, every title the same except with a different girl from a different decade of American history. They were predictable; they were informative. I learned a lot about mainstream history: cholera and the Underground Railroad and D-Day and the first Earth Day. Most of all, though, I liked the sameness American Girl preached, the idea that every girlhood was the same, was equal, when you boiled it down to its structured format.

See. I was boring as hell.

Don’t get me wrong, I did read other books. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess and The Secret Garden, for instance. I loved Kate DiCamillo and Sarah Weeks. A bunch of children’s books about the Holocaust, like Lowry's Number the Stars and Joan Wolf’s Someone Named Eva, all dark and vivid and safely rebellious. And they were good books, truly. I still love many of them. They were shiftless, though, often lacking adventure. Conventional, in many ways. Usually containing a blonde girl who finds herself through a hero’s journey of some sort that never really feels that heroic.

I was a late bloomer. I’m still blooming.

I eventually read the 21st century classics: Rowling, Riordan, Levine, Stewart, Collins, Roth, Clare, Green. I went through the Stephanie Meyer phase (in case you were wondering, I was Team Edward). I adored the horrid, ghostwritten Maximum Ride novels that got worse and worse as more and more were savagely released. I got my adventures, my girl-meets-boy-vampire/werewolf/warrior/angel novels, my romance, my Dark Lords and fight scenes, my sex, my demigods and wizards, my fixture of youth literature.

The problem was exactly that. I had skipped a generation. I had gone to YA before I had properly finished middle grade. I entered college and had missed out on a long list of children’s literature, filled with adventure and love and nonconformity and actual diversity, something that is sadly still uncommon in even YA literature.

Last summer, my best friend convinced me to read Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, a postmodern, absurd, hellish and hysterical set of novels following the lives of three miserable siblings. As an adult reader, I immediately recognized the intertextuality in Snicket’s (or, his real name, Handler's) work, from his homage in The Reptile Room to Nabokov’s Lolita, which I had read just weeks before, to his orphan protagonists Violet and Klaus, who recall the disenfranchised nineteenth century child characters of Hardy’s Tess and Brontë’s Jane respectively. My friends, who had read A Series of Unfortunate Events as children, were often surprised and excited by the things I picked up on in the books, wondering why they had not realized what they were reading. But they should not have been shocked or disappointed in themselves: I had already read Victorian literature and the modernists by the time I got around to Snicket’s famous series. I was the abnormal one, not them.

I have recently continued the spree to make up for my lost childhood. I destroyed L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time over winter break, just in time to watch the filming of Ava DuVernay’s new adaptation over the social media accounts of the newest Meg Murray (Storm Reid), Calvin (Levi Miller), Mrs. Which (Oprah Winfrey), and DuVernay herself. In my conventional childhood, I somehow missed Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, so I picked that up too. I’ve added Pam Muñoz Ryan’s Esperanza Rising and Katherine Paterson’s The Great Gilly Hopkins to my summer reading list. I’m excited to be working right down the street from the New York Public Library, which has an extensive children’s room. I’m sure walking into my office with middle grade novels will raise more eyebrows than walking out of the children’s section with them will.

When I’m found reading children’s novels by peers, I’m often questioned on whether I’m going through a nostalgia phase or something. Funnily, this is no nostalgia; this is discovery. My admittance of my ignorance often leads to another question: why do you want to read children’s literature as an adult?

Now, naturally, I want to read children’s literature because I enjoy children’s literature. I do, indeed, want to find the “missing” puzzle pieces of my literary childhood and put them in their places. I also am interested in studying children’s culture and education, which is often the most suitable answer to mildly curious questioners. But most of all, I’m interested in the complexity in children’s literature–the same complexity in children themselves that is often overlooked by the adult world.

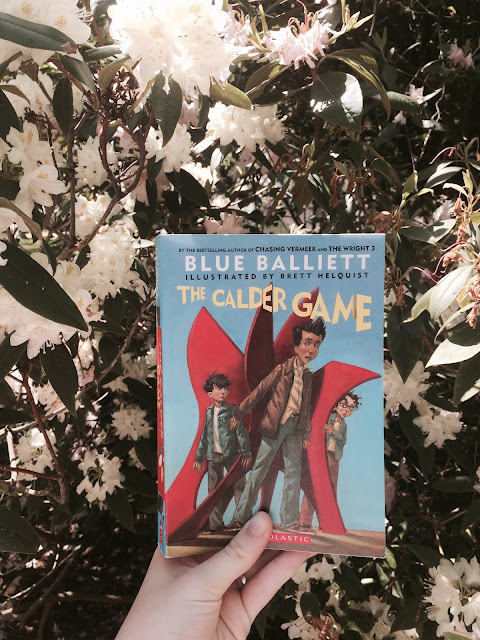

Take, for instance, Blue Balliett’s Chasing Vermeer novels, which I finally read this past month. First published in 2004 and followed by two sequels, Chasing Vermeer follows sixth-graders Petra and Calder on an adventure of coincidences and stolen art in Chicago’s Hyde Park. The first novel and its following installments are not only intriguing and complex mysteries but also contain extended references and cross-references to famous artists, writers, historical events, and mathematical practices. Balliett’s stories are loaded with questions about philosophy, architecture, art, and humanness, and her writing cannot be labelled as simplistic simply for being for children. One wholly impressive example lies in Balliett’s third book, The Calder Game, where twelve-year-old Calder goes missing at the same time that an Alexander Calder statue is stolen. When Calder describes being trapped in a space with very little oxygen, Balliet’s narration nears stream-of-consciousness:

By the time all was black again, he realized that it was warmer in his little cave. Not warmer, no, steamy. Airless.

His headache was becoming close to unbearable. He licked water off a rock and curled up again into a ball, whimpering now, and tried to picture the clean-edged pieces in the cool, dark water of the Cascade. If only they landed in a shallow pool, if only they weren’t swept downstream, if only, if only.

Wish, wish, wish. Suddenly, the word was beautiful, fluid and free in the water and stone and darkness that had become his world. His heart was pounding, and he felt the word beating in his veins: Wish, wish, wish. (326)

Calder’s experience adds to the overall excellence of Balliett’s work, which incorporates intense scholarly discussion at a level that children can understand. Additionally, Balliett’s urban setting introduces her readers to a real landscape. Her characters too, at least, feel real: the rivalry between Petra and Calder’s best friend Tommy, for instance, reveals the struggles of childhood friendships. Additionally, Balliett has something in her novels that children’s literature, now over ten years since her first book was published, is still working on: diversity. All of Balliett’s main characters are people of color; one child has four siblings, another has a single parent; and, though not explicitly, Balliett implies socioeconomic differences between the child characters and their families. She actively works to add diversity to children’s literature, both in setting and in character circumstance, a pursuit that, still today, is sought by the publishing industry and organizations like We Need Diverse Books and Kids Like Us.

It is the complexity of works like Balliett’s that calls me back to children’s literature. It is the complexity of childhood that lures me back to child characters, narrators, and realities. Children’s literature can and has pushed boundaries. A Wrinkle in Time integrates religion and science. Harry Potter presents genocide. A Series of Unfortunate Events questions conventional morality. Twain’s thirteen-year-old Huck questions slavery and racism years before Brown v Board was able to occur.

This is not to say that children’s literature does not have a long way to go when it comes to diversity and complexity. It does. But so does “adult” literature and literary studies. It was not until very recently that my college added a Diversity of Literatures requirement for the English major. Just as children’s literature should be held to the same standard for diversity as adult literature, children’s literature should be given the credit it deserves when it comes to its merit. Children’s novels, like children, do not deserve to been deemed as less-than, incapable of complexity except on rare occasions, or undeserving of study. I am a prime example of this mistake, for when I skipped significant stories as a child, I found myself lacking in experience and understanding compared to other literary peers. A Series of Unfortunate Events could make English majors just as often as To the Lighthouse does; Hermione Granger is more of a literary icon for my generation than Elizabeth Bennet ever will be; L’Engle is as important as Dickens today.

So let’s talk about children’s literature. Seriously this time.

Comments

Post a Comment